What Orson Welles Teaches Us About Being Independent

He suffered for being indie – but we don't have to.

I currently have an unobstructed view of Jupiter from my window. Only the brightest stars can cut through the sky’s glow in New York City. Jupiter, a pinprick of light in an otherwise empty winter sky, is the largest planet in our solar system—but it’s far from the biggest thing out there. Massive superstars like Betelgeuse (Betelgeuse, Betelgeuse!) dwarf our sun several hundred times over. There are trillions of stars we can’t see, their light too distant and faint.

As I work on the next page of my webcomic, I think about the energy I put into it. I wonder if I’m being irresponsible, pouring so much effort into a project no one asked for. Like the hidden stars around Jupiter, my work exists in anonymity. Across the city, countless other artists are working just as hard on their own unseen creations. Our job isn’t just to make our projects real—it’s to bring them closer, so they can be seen.

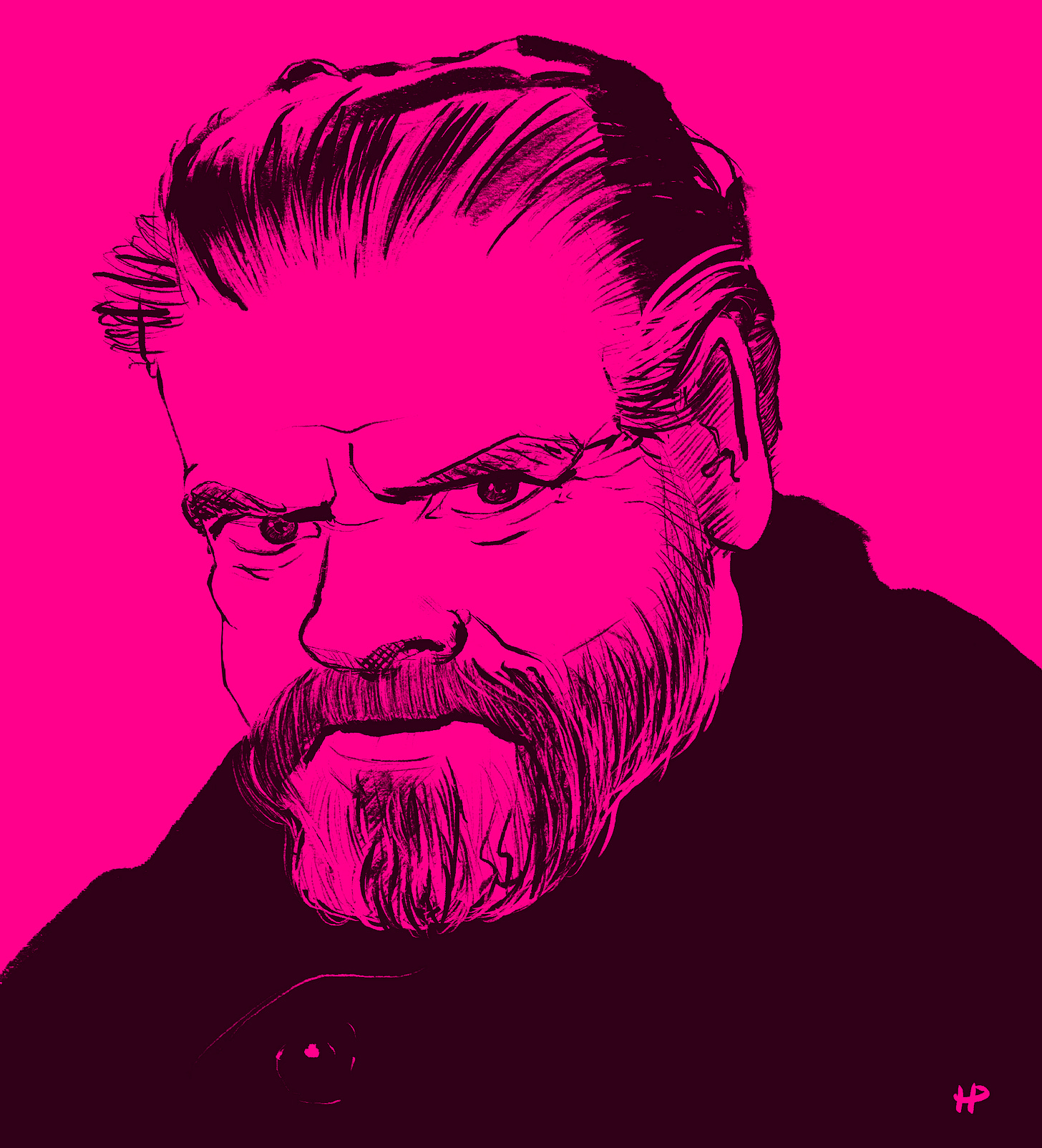

Lately, I’ve been listening to interviews with director Orson Welles on YouTube while I work. His creative projects radiated a brilliance that could cut through any sky. Learning that his independence ruffled feathers, fills me with confidence. If someone of Welles’ stature could struggle with creating work his way, then I’m not alone. Before Welles became a director, he wanted to be an artist. In a B

BC interview series titled Orson Welles’ Sketchbook from 1955, he illustrates his stories as he speaks. I recognize his style. It’s alive, spontaneous and urgent. My favorite teachers in art school drew like this.

The way he scratches ink onto the page reveals a person who doesn’t see mistakes. He uses a combination of thick and thin lines to build his drawing in layers. Yet, impatience creeps in. There’s a moment in the video where it’s clear he’s unhappy with what he’s done. His focused movements dissolve into frantic scribbles, an almost destructive energy takes over. He seems to forget—or simply not care—that he’s being filmed. Then, as if nothing happened, he turns in his chair, faces the camera with a boyish smile, and starts telling his story.

Why does Orson Welles’ star shine so brightly? Why not the countless artists who drew better or the directors who made more movies? The answer is simple: he created Citizen Kane, arguably the most important film in history. At just 26 years old, he made a project that forever changed the way people view cinema. There is before and after.

It’s an oversimplification to say Orson Welles “made” Citizen Kane. Hollywood’s immense power was behind him. A movie studio, convinced of his potential after his riotous adaptation of War of the Worlds, granted him unprecedented creative control. He also had the collaboration of Gregg Toland, one of the most experienced cinematographers of his time, who leveraged Welles’ inexperience by making sure everything he asked for was done. Welles said that at the time he didn’t know he was breaking any rules. He just knew what he wanted. Together, they invented groundbreaking techniques.

We know money and power can’t guarantee success. That’s up to the audience. For Welles’ vision to become reality, countless circumstances had to align perfectly. Later in life, Welles lamented having fallen in love with filmmaking because it required so much effort from others. He wished he could have been more independent.

While Orson Welles accomplished a lot, he was deeply tormented by the projects he couldn’t make. In one interview, he talked about the high cost of filmmaking and his frustration at being unable to finance his movies. Citizen Kane was a critical triumph, but it provoked the ire of powerful figures—most notably William Randolph Hearst, one of the wealthiest Americans of his era. (The film was originally titled The American.) Its not-so-thinly-veiled critique of Hearst led to a fierce backlash. Hearst’s team worked to bury the movie and tarnish Welles’ reputation, turning him into a pariah. Welles’ days of creating blockbuster films effectively ended with Citizen Kane.

What I’ve learned from Orson Welles is this: the machine is not meant to work for you, so make your own own. It’s a lot of extra work, but it’s worth it. While brands like Instagram and WebToons allow you to self-publish, they don’t allow for creative freedom. Using HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, I can control how my work appears and ensure it aligns with my vision—something no external product can fully provide. This independence allows me to focus on making my work the best it can be.

I don’t want to give the impression that learning to code is easy. I struggled with math in high school, earning C’s and D’s. I now understand that my ADHD made traditional learning challenging. My brain processes information differently, but that doesn’t mean I can’t learn. Teaching myself programming syntax was a slow process. I tackled one lesson at a time until I grasped the basics. Yes, it required a time investment, but the payoff is lifelong.

I publish my project one page at a time and listen for feedback. While I hope it resonates with people, it’s okay if it doesn’t achieve a massive readership. What matters isn’t how big I make my project, but how close it is to you, its audience.